Over the past couple of months, my 9-year old son has repeatedly told me that he wants to be a professional football player when he grows up.

This got me thinking about the ultra-competitive spirit I had when I was young.

For several years while growing up, I really thought that there was a legitimate chance that I could be a professional athlete. This belief fueled an extremely competitive nature to the point in which I was willing to do just about anything to be victorious in even the least significant athletic activities.

Then one day, when I was about my son’s current age, a family friend broke the truth to me. I vividly remember his words: “Son, you ain’t strong enough or fast enough to make the pros.”

Tough words for a preteen, but I guess he was just being honest. I think his motivation was good. He did not want another low-income kid thinking that he was going to get rich quick by being a professional athlete at the expense of focusing on his studies.

Many children think they are going to be professional athletes, but most youth-league “superstars” find themselves hobbling into late adulthood, dreaming about what could have been. There is a reason why so many people can relate to Napoleon Dynamite’s uncle Rico. They are him.

I ignored the family friend that broke the “truthful” news to me. He was old. I was young. He missed out on his dream. I was going to accomplish mine. Throughout my middle school and high school years, I would internally put all naysayers on notice: “Yo haters! Get out my way!”

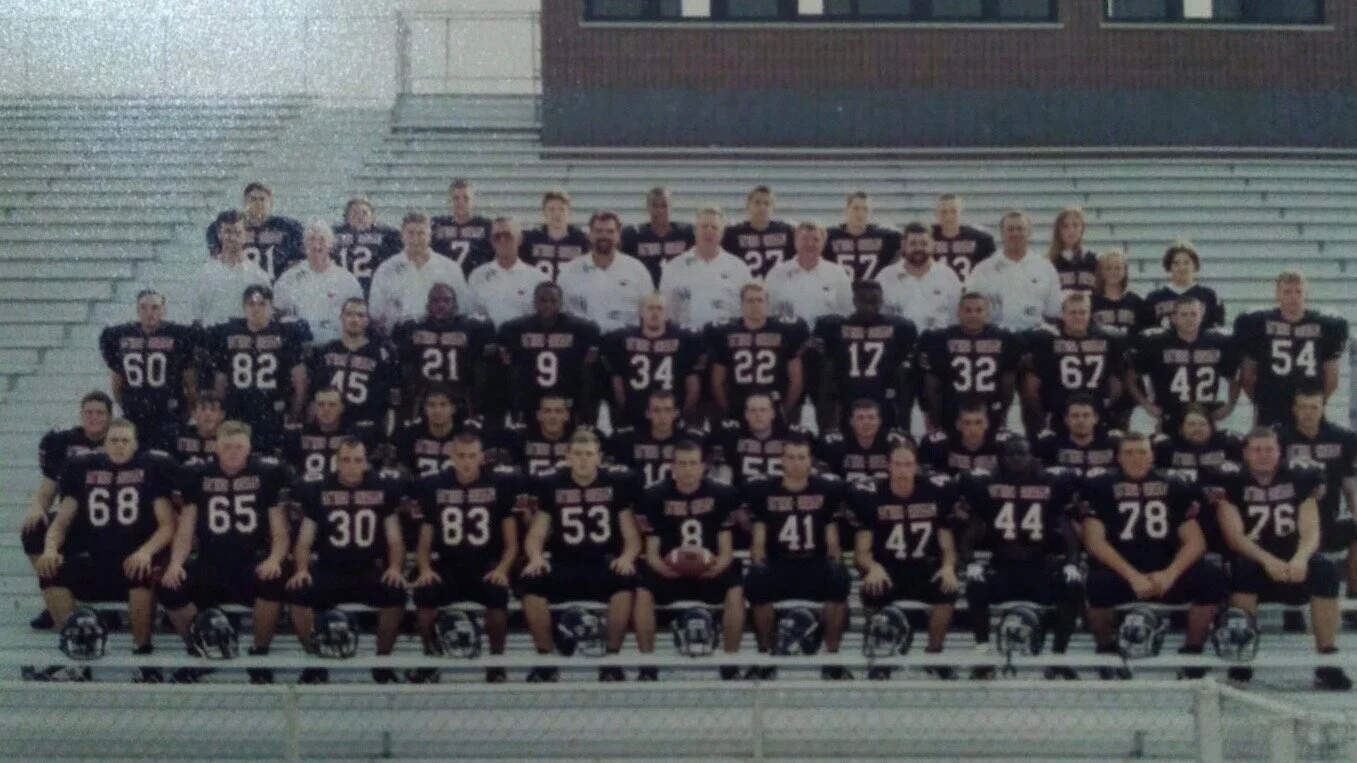

My first player picture. I was in the 8th grade — 1993.

I never really had that growth spurt that people talk about. This meant by the time I started playing high school football, I was 5’ 8” tall and weighing in at a mere 165 lbs. My body muscle index was completely unremarkable for a young man who insisted on playing on the offensive line and on the linebacker corps. After spending a year as captain of my middle school football team, I had convinced my ultra-competitive self that it would be a failure if I was not a starter on the varsity football team by my junior year in high school (11th grade).

How was I going to build the muscle mass necessary to compete at the high school level with people who were naturally bigger, stronger, and faster than me?

The answer: Supplements.

At the age of 15, I was introduced to creatine monohydrate by my head football coach.

Between my sophomore and junior years of high school, I bulked up about 20-30 lbs. by taking creatine and lifting weights. One of the reasons why I took the powder was because of the ambition that I sense to achieve my goal of being a starter. However, the primary reason why I started taking it was because my coach told me to.

My father passed away when I was five-years old. While going through some pretty rough teenage years, I started looking to my coaches as father figures. They began filling the void that I sensed in my heart for a father. I would see them every single day; they controlled what I did in my life even down to my schedule and the food that I would eat—like creatine, which got me pretty muscular (and a little chubby), by the beginning of my 11th grade football season. I went into summer football camp with high expectations of being a major player on a team that was highly ranked in the region. It was the summer of 1996. I was 16 years old. I had newfound muscles. There was nothing that was going to stop me.

On one of the first days of summer camp, the dream came true. I was put in with the first team of linebackers.

A couple of plays into the scrimmage, the coach reprimanded me for reacting improperly to an offensive blocking scheme. I took it on the chin because I was playing well. Then, in what I am now convinced was an attempt to make sure I was obeying him, the coach ran the same offensive play at me. I, without thinking, reacted to the play exactly the way the coach had just told me not to play.

After hearing the whistle, I lifted up my head to see the coach charging at me. Then, he got uncomfortably close to me. Then, really close. Then, the coach unexpectedly grasped and lifted my face mask with his left hand so that my face was exposed and repeatedly struck me with his right hand. He hit me at least 5-6 times in my jaw, neck, and front of my face.

All of the other adult coaches who were teachers stood around and watched him do this. No one said a word to him.

All of the teenage players stood around in shock. No one said a word to their coach.

Then there was an awkward moment of silence as everyone stood in shock. The coach stormed off, red-faced and unapologetic.

One of the coaches blew a whistle and called for a rare water break.

I walked over to the water bottles from the field, trying to pretend that everything was fine.

Everything was not fine.

My face didn’t really hurt. The pain that I felt inside was far greater than the minor abrasions I now had on my face. During that short walk to the water cooler, I briefly reflected upon all of the time and the effort that I had put into football. In that moment, I contemplated the fact that I had mostly worked hard over the past year to impress the coaches who were like my father figures. The person who I wanted to impress most, my head football coach, had terribly abused his power by hitting me physically and crushing me emotionally.

During this past Holy Week—nearly 24 years after the events I just recounted—I began reflecting upon this incident once again. Let me explain why:

For many years, I thought that coach would contact me and apologize. I would see him at reunions and high-school functions and he was always extremely cordial toward me and shared concern for my family. Yet, there was always sort of an “elephant in the room” that prohibited our conversations from transcending small talk. I was convinced that someday, coach would pull me aside at one of these events and apologize for having hit me in my face—for having lost his temper and abused his authority as a coach. I was sure we would hug and move on with our lives.

This conversation never happened.

Not too long ago, I read via Facebook that coach passed away. He was 80.

This conversation will never happen.

Since coach’s death, I have thought about what it looks like to forgive someone who has wronged you that will never ask you for forgiveness. I fully recognize that there are situations in which people have been wronged in distinctly more harmful ways than a couple of facial scrapes at football practice. However, the same question applies: What do we do when people harm us, and we never receive a formal apology?

I have realized that, on the one hand, it is impossible for me to forgive the way God forgives. What I mean by this is that I cannot absolve people of their sin. In my case, it is not humanly possible for me to pardon the wrongdoing that this person committed against God through his anger and abuse. There was an element of what this person did that was distinctly between him and God.

On the other hand, I can forgive in the sense of intentionally striving to fend off the natural sentiments of anger and resentment that arise as a result of being wronged. In so, I surrender my “right” to be angry with the aspiration that my resignation of personal vindication would be a tangible example of the type of forgiveness people can receive by turning to God through Christ.

I realized this a couple of weeks ago while reading through the Passion narrative just prior to Easter Sunday. Jesus was the ultimate example for humans of how to practically forgive. This is particularly demonstrated in one of Christ’s sayings from the cross: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.” (Luke 23:43).

Upon reading this passage, my feeble mind protested:

“Wait a second, Jesus!”

“They just unjustly accused you!”

“They just punched you!”

“They just spat in your face!”

“No, Jesus, no! Let them dread their own punishment for the years to come, wondering if they could ever be forgiven for what they did to you!

“No, Jesus, no! Do not let them off the hook without them apologizing for what they did to you! Look at how they have humiliated you, making you look so weak despite you being the king of the universe!”

Jesus was so strong in his weakness.

Despite the unjust treatment of Jesus, and the physical abuse eventually resulting in his physical death, Jesus, audibly prayed while hanging on the cross that these same peoples’ relationship with God would be restored. Jesus notified all those who were willing to listen to him that he would not harbor anger toward them for abusing him. Jesus would not take resentment to the grave. Jesus’s example of forgiveness transcends the Passion week into the lives of his followers in that we have a practical example of what to do as we strive to forgive those from whom we may never receive an apology.

Jesus prayed to God for those who had sinned against God to be forgiven. Jesus was concerned about those around him being absolved of their wrongdoing by God. Jesus prayed aloud, permitting those who had wronged him to hear him. In this, we observe that Jesus let people know that he was not set on holding their wrongdoing against them.

Jesus then died on the cross with all of those who were within earshot knowing that they needed to be forgiven by God for participating in his unjust murder. At the same time, Jesus demonstrated that he was not willing to die without letting everyone know that he surrendered that right his right to vindication because he desired that their relationships with God would be restored.

My football years - Fall 1994

Jesus’s example was followed by Stephen—the first Christian martyr recorded in the scriptures. While Stephen was being unjustly stoned, he cried out, “Lord, do not hold this sin against them,” (Acts 7:60). Like Jesus, Stephen used his final breathes to appeal to God for his offenders to be forgiven of their wrongdoing. In this, Stephen announced to all of those stoning him that he would not go to the grave bitter toward his murderers. Like Jesus, Stephen was more concerned about those who wronged him being forgiven before God, than holding on to any interest in vindication.

I am convinced that there can be forgiveness by those who have been wronged without full restoration with the wrongdoer. Optioning to release someone from (even) just indignation and pointing them toward restoration with God, does not mean that 1) we are compelled to take up social acquaintance with that person or 2) that proper disciplinary or judicial action is inappropriate. Indeed, there must be a system of consequences safeguarding against injustice and abuse if there is to be any semblance of order in society at large, or smaller organizations.

I would have loved to have the opportunity for restoration with coach. I would have loved the opportunity to draw closer to him as a person in my post-competitive days. I would have enjoyed following his life as he aged.

As I reflect on him hitting me years later, I recognize how serious his offense was. Coach was wrong for what he did in that he intentionally physically assaulted me for not doing what he expected of me. There was no reason for what he did and his reaction was completely inappropriate.

I would have formally forgiven him in person if he were to have asked for forgiveness because my heart was not bitter toward him. Unfortunately, this in person conversation did not happen.

But, I did forgive coach. I forgave him a very long time ago.

Even in my immaturity as a ridiculously ambitious adolescent, I forgave coach just seconds after the incident. As I walked toward my water bottle, I realized that i needed to release any anger directed toward him because only God could change his heart. On that same football field during those awkward moments of silence of that hot summer day, God permitted me to forgive.

I may not have ever had what it took to be a professional athlete—and I may have held on to that dream for too long. However, with Christ as my example, I have all that I need to practice forgiveness—and I do not have to hold on to the wrong done to me.